Translate

Saturday, December 20, 2025

Friday, December 19, 2025

Religious Brutality

“The man who was lynched, hung from a tree, and burned to death in Bhaluka, Mymensingh on allegations of religious blasphemy was named Dipu Chandra Das. He was a garment worker.

His father is physically disabled. It can be said that he was paralyzed due to some accident. Leaning on others’ shoulders, he stood there crying. His son was the family’s sole breadwinner. He is survived by a one-year-old child.

The incident took place on Thursday night in front of Section-3 of Pineo BD Limited factory in Jamirdia Dubalia Para of Habirbari Union under Bhaluka Upazila.

The deceased, Dipu Chandra Das, was the son of Rabi Chandra Das from Tarakanda Upazila of Mymensingh and was a worker at that factory .

.

According to the family, since he had passed a BA degree, he performed supervisory duties. They believe that due to some argument at the garment factory, certain people brought accusations of religious blasphemy against him. In front of his family members, he was stripped naked, beaten, hung from a tree, and burned to death.

How such monstrosity can become an ordinary occurrence in Bangladesh—this is clearly barbarism. The core objective is to drag this country back into a dark age.”

Thursday, December 18, 2025

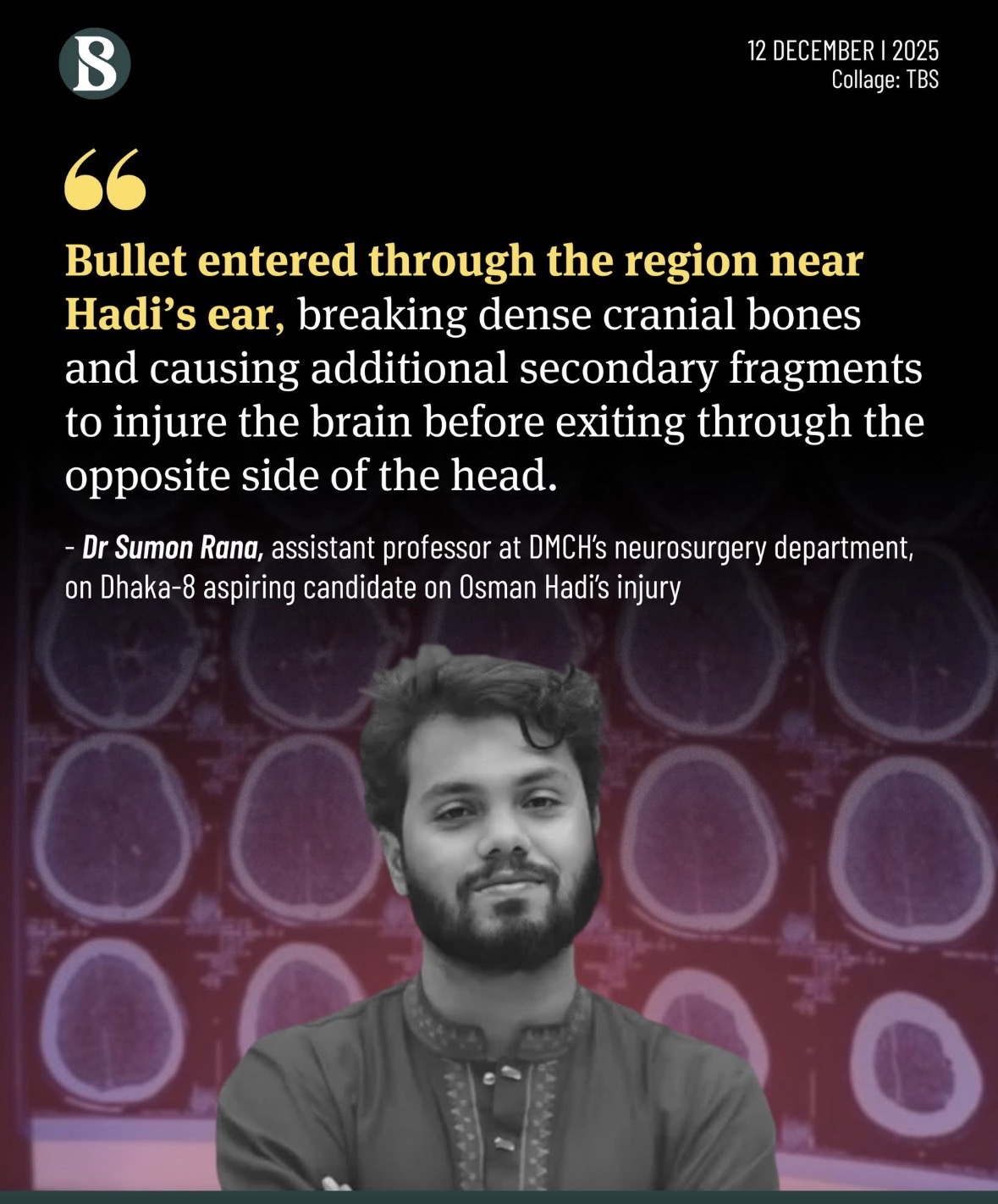

Bangladeshi leader and July uprising figure Sharif Osman Hadi shot dead

Sharif Osman Hadi, a prominent Bangladeshi political activist and aspiring independent parliamentary candidate, has died after being shot in the head earlier this month, Bangladeshi media reported on Thursday.

Hadi, 33, died while undergoing treatment at Singapore General Hospital at around 9:30pm local time on December 18. He had been in critical condition since the attack on December 12.

The official Facebook page of Inqilab Moncho announced his death late Thursday night local time. In a statement, the group said: “The great revolutionary Osman Hadi has been recognised as a martyr (Shaheed) by Allah for his struggle against Indian imperialism.”

Hadi was the convener and spokesperson of Inqilab Moncho, a youth-led political and cultural platform, and had recently announced plans to contest the upcoming Jatiya Sangsad national parliament elections as an independent candidate from the Dhaka-8 constituency, a key seat in the capital.

Hadi, who was widely seen by supporters as one of the most prominent faces of the July 2024 uprising, later announced plans to contest the election, positioning himself outside Bangladesh’s traditional party structures.

Shot in central Dhaka

According to police and eyewitness accounts, Hadi was shot in broad daylight on Friday afternoon in the Paltan Bijoynagar area of central Dhaka, shortly after Friday prayers.

Police said the attackers arrived on three motorcycles near Box Culvert Road, a busy commercial and office area. One of the assailants opened fire at close range, with the bullet striking Hadi’s left jaw and head, before the attackers fled the scene.

He was rushed to Dhaka Medical College Hospital, where he was admitted to the intensive care unit. Due to the severity of his injuries, he was later transferred to a private hospital in Dhaka and subsequently airlifted to Singapore on Monday for advanced treatment.

Family members said doctors in Singapore were unable to perform surgery because of his unstable condition.

Death threats before the attack

In the weeks leading up to the shooting, Hadi had publicly stated that he was receiving death threats.

In a Facebook post dated November 14, he wrote that he had been threatened with being killed, having his home set on fire, and sexual violence against female members of his family. The post resurfaced on social media following news of his death, prompting widespread anger and renewed calls for accountability.

Just hours before the shooting, Hadi had shared another Facebook post related to his election campaign, noting that he had not put up posters in the Dhaka-8 constituency.

Political reactions and protests

Following confirmation of his death, condolences and reactions came from across Bangladesh’s political spectrum.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party, Bangladesh Jamaat e Islami, National Citizen Party, and Islami Andolan Bangladesh issued statements mourning Hadi’s death and calling for those responsible to be brought to justice.

Student groups and supporters staged protests at Shahbagh, a central protest site in Dhaka, demanding the immediate arrest of the perpetrators and criticising what they described as delays in the investigation.

Protesters also called for the resignation of Home Adviser Jahangir Alam Chowdhury, a retired army general, accusing the authorities of failing to maintain law and order as the country prepares for national elections scheduled for February 2026.

Investigation and alleged flight to India

Bangladesh police said they have arrested at least 14 people in connection with the attack.

Law enforcement agencies identified Faisal Karim Masud as the alleged shooter and Alamgir Sheikh as the motorcycle driver. According to police and Rapid Action Battalion officials, both suspects illegally crossed into India through the Haluaghat border in northern Mymensingh district following the attack.

Two individuals accused of assisting the suspects in crossing the border were produced before a Dhaka court earlier this week and placed on remand for interrogation. Investigators said they are examining who planned and financed the attack.

Bangladeshi authorities indicated that, if the suspects’ presence in India is confirmed, diplomatic engagement would be required to secure their arrest and return.

Concerns over political violence

Hadi’s killing has renewed concerns about political violence and election-related insecurity in Bangladesh.

Rights groups and opposition parties have warned that activists and candidates, particularly those operating outside established political parties, face intimidation and attacks as the election period approaches.

As investigations continue, Hadi’s supporters have said protests will continue until those responsible for his killing are held accountable.

A young man beaten to death in Mymensingh over allegations of religious blasphemy.

A Hindu youth was beaten to death by a group of people in Bhaluka, Mymensingh, over allegations of religious blasphemy.

Police said the incident took place on Thursday night in the Dubalia Para area near Square Master Bari in Bhaluka upazila.

After beating the youth to death, the attackers also tied his body to a tree and set it on fire, Bhaluka police station duty officer Ripon Mia told BBC Bangla.

Police identified the deceased as Dipu Chandra Das. He worked at a local garment factory and had been living in the area as a tenant, according to preliminary information from officials.

“An agitated mob caught him around 9 pm on Thursday and lynched him for allegedly making derogatory remarks about the Prophet. After that, they set fire to his body,” duty officer Mia told BBC Bangla.

Police later reached the scene and brought the situation under control. The body was recovered and sent to the morgue of Mymensingh Medical College Hospital, officials said.

No case has been filed so far.

Tuesday, December 16, 2025

Prominent leader of Bangladesh’s July Uprising Hadi shot in broad daylight

The shooting of Sharif Osman bin Hadi, an independent candidate in Dhaka-8 and convener of the Inqilab Moncho platform, a day after the election schedule was announced has sparked intense debate in the political arena.

According to sources involved in the investigation, the attack was carried out after several months of planning, with the intention of creating large-scale instability in the country. An escape plan was also put into effect immediately after the attack.

Friday, December 12, 2025

Attempt to Murder

Sharif Osman Hadi, the spokesperson for Inqilab Mancha, was shot in the head by unknown assailants on motorcycles in the capital's Paltan area today (12 December), according to police and witnesses.

Sharif Osman Hadi, the spokesperson for Inqilab Mancha, was shot in the head by unknown assailants on motorcycles in the capital's Paltan area today (12 December), according to police and witnesses.

The incident took place a day after the Election Commission announced the schedule for the 13th national parliamentary election.

Hadi, an aspiring independent candidate for Dhaka-8 constituency in the upcoming polls, was rushed to Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH) emergency department following the attack and was taken to the operation theatre at around 3:50pm, DMCH Police Outpost In-charge Inspector Md Faruk confirmed to The Business Standard.

Later, around 7:30pm, after his surgery, he was taken to Evercare Hospital for advanced treatment, DMCH Director Brigadier General Md Asaduzzaman told reporters.

Dr Zahid Raihan, head of the Neurosurgery Department at DMCH, told reporters in the evening that Hadi's condition is "extremely critical".

Monday, November 17, 2025

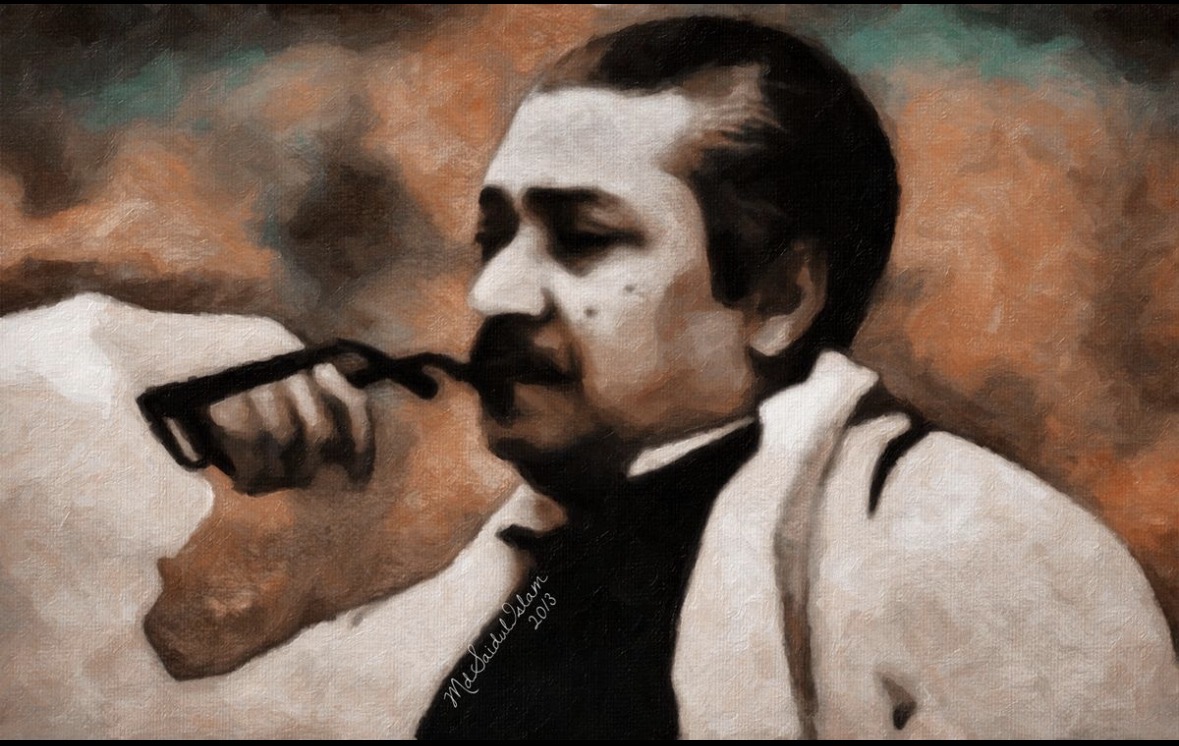

Mujib’s Dark Side: A Controversial Chapter

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the great leader of Bangladesh’s independence—respected as the Father of the Nation. However, like every historical leader, his tenure had both light and dark sides. Today’s discussion focuses on that ‘dark side’ which researchers and critics have debated.

1. Famine and Corruption (1974)

During the 1974 famine, nearly 1.5–1.6 million people died. Although food was available in the market, syndicates, corruption, and failures in the distribution system prevented ordinary people from getting it.

👉 Historian Naomi Hossain says, “The famine was the main reason for the decline in Awami League’s popularity.”

2. Repression by the Rakkhi Bahini

Formed in 1972, the Rakkhi Bahini was initially tasked with maintaining security but soon became a symbol of fear.

- Suppression of opposition parties

- Extrajudicial killings

- Abductions and torture

These actions angered the general public.

👉 Badruddin Umar says, “The Rakkhi Bahini alienated the Awami League from the people.”

3. BAKSAL and One-Party Rule

In 1975, he formed BAKSAL, abolishing all political parties and establishing a one-party system.

- Control over newspapers

- Suppression of political opposition

- Restriction of civil liberties

👉 Critics see this as the death of democracy.

4. Arrogance of Leadership and Public Discontent

Sheikh Mujib was charismatic but, according to critics, sometimes became arrogant.

- Allegedly did not pay enough attention to the suffering and hardships of the people.

- Especially the lower-income class suffered the most during the famine, but their plight was largely ignored by the state.

5. Absence of Public Mourning after the Assassination

When he and his family were assassinated on 15 August 1975, many people reportedly celebrated in the streets and distributed sweets.

👉 Professor Naomi Hossain says, “There was hardly any visible public mourning.”

This indicates that by the end, he had lost the trust of the people.

Conclusion

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is undoubtedly the father of independent Bangladesh. But in the later years of his leadership, famine, corruption, repression by the Rakkhi Bahini, BAKSAL, and alienation from the public are marked as his dark side in history.

A great leader can give birth to a nation, but poor policies and decisions can also provoke public anger—this is the greatest lesson of Sheikh Mujib’s governance.

“Exploitation of Bangladeshi Women in Saudi Arabia: Brokers, Slavery, and Legal Gaps”

Rape happens in every country in the world, but the situation in Saudi Arabia is somewhat different. Saudi Arabia is a country where a Bangladeshi woman who went there for work can be raped in the morning by one man, and at night the son of that same man comes and rapes her. It is unclear whether there is any other country where a father and son together rape the same woman in this manner.

Many might ask what Islam has to do with this. The fault lies with the people committing the crime; Islam itself has no blame. Those who say otherwise are mistaken. They do not realize that in Saudi Arabia, Bangladeshi women are raped under the pretext of Islam. Until now, there is no precedent in Sharia courts of Saudi Arabia where a citizen has been punished for raping a Bangladeshi woman.

Most of the women who become victims of rape in Saudi Arabia are those who fall prey to brokers. Because these women are poor and uneducated, they do not realize that they did not come abroad through a legitimate agency. Broker networks primarily sell these women to Saudi sheikhs. The women themselves are often unaware that they have been sold; they think they have come as contractual laborers, but to the sheik who has “bought” them, they are not laborers—they are slaves.

In Islam, sexual relations are permitted only with a wife or a female slave. Female slaves can only be obtained in two ways:

- Captured in war

- Purchased from the market

Saudi sheikhs primarily buy Bangladeshi women from broker networks. According to Sharia law, these women are considered slaves in the eyes of the sheikhs, and sexual relations with them are considered lawful. This is why there are no recorded cases in Saudi Arabia where a citizen has been punished for raping Bangladeshi women.

Reference

- Bangladesh: Domestic Workers Tell of Sexual Abuse in Saudi Arabia — Benar News https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/bengali/domestic-workers-10162019171510.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Bangladeshi domestic workers face abuse in Saudi Arabia — DW https://www.dw.com/en/bangladeshi-domestic-workers-face-physical-and-sexual-abuse-in-saudi-arabia/a-45401227?utm_source=chatgpt.com

The Story of Jamir Hossain: A Life Lost to Injustice

The man’s name was Jamir Hossain. He was a bus driver. For the allegation of reckless driving that caused the deaths of Tareque Masud and Mishuk Munier, he was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2017. Three years later, while serving his sentence, he died of heart failure.

To punish the bus driver, the cultural elites kept provoking the public through their media. For example, in 2016 Bangla Tribune wrote:

“Tareque–Mishuk’s dreams—crushed and twisted—have not yet seen justice.”

After the verdict in 2017, an excited Prothom Alo wrote:

“Reckless bus driver gets life sentence.”

Yet this bus driver was innocent. BUET professor Dr. Shamsul Hoque showed in his investigation that the bus driver was completely innocent.

Because he was poor, the cultural elites used the state apparatus to kill Jamir Hossain. Perhaps Tareque and Mishuk’s dreams were shattered, but Jamir Hossain’s entire family was devastated too. He must also have had dreams—dreams of bringing better days to his family. That never became possible, because he and his dreams were killed.

Look Back-

- Bangladeshi film‑maker Tareque Masud dies in car crash — The Guardian

- Award winning filmmaker killed in road accident — NDTV